In North America the phrase “home town” is a common one. When asked the location of my home town I immediately think of Bridgwater, in the beautiful county of Somerset, UK. My home from 1953 to 1966 was in the stable block at Halswell Park, Goathurst, just four miles from Bridgwater in the direction of the Quantock hills. After graduating from Enmore primary school at age ten I was educated in Bridgwater, at Bridgwater Grammar School for Girls.

Bridgwater is famous for many things, including the odour from the cellophane factory in past years, but for me two things come to mind: Bridgwater Fair and Admiral Blake. The Fair and Carnival have their genesis in medieval times, and the community participation involved in staging the carnival is unparalleled. But it is Bridgwater’s rich history of radical dissent that makes it such a special place.

This post is about slavery, Robert Blake, and the remarkable town of Bridgwater in years past. Robert Blake was born in 1599 into a Bridgwater merchant family at a time when Bridgwater was a thriving port (it even rivalled Bristol). In later years he became a brilliant military leader, first on land and then at sea. He was a huge asset to the parliamentary cause during the English civil war, and it is perhaps fortunate that he died at sea in 1657 and was not around to witness its defeat. The English republic was short lived, and monarchy was restored upon its demise.

Blake never owned or traded slaves, and in fact there is documented evidence of him freeing African slaves held by Barbary pirates. He did have a black servant (one of three) called Domingo. In his will he left ten pounds to each of his other servants, but fifty pounds to Domingo who was clearly a favourite.

Robert Blake was a Puritan, as were many of Bridgwater’s non conformist inhabitants. Slavery was offensive to their religious principles. In the late 17th century huge wealth was created, either by the slave trade directly or from industries like sugar, cotton and cocoa that were underpinned by slave labour. The City of Bristol was a major beneficiary, but not Bridgwater.

True to type, the good citizens of Bridgwater continued to be on the wrong side of history during the Monmouth rebellion, the last armed conflict on English soil. Establishment vengeance (King James II), was especially harsh with the ringleaders hung, drawn and quartered. Those who escaped death were destined for slavery. In 1685, after the rebels lost at the Battle of Sedgemoor, 612 Somerset men were transported to the West Indies where they were auctioned off as slaves.

Surprisingly, all who had survived the sea journey and subsequent hard labour, were given a full pardon after four years. Why? My theory is that the existence of white slaves from the home country was an uncomfortable contradiction to the evolving narrative around the inferiority of Black people from Africa. The slave owners might flog their slaves during the week and attend church on Sunday. This could only be possible if they had internalized the prevalent propaganda around racial differences. Also, lets not forget the Bridgwater spirit of non-conformity (and support for lost causes like the Duke of Monmouth). They may have been perceived as potential agent provocateurs among the Black slave population.

Whatever the reasons for the pardon a few did make it home to Somerset (many would not be able to afford the return fare). They would tell their stories, which must have been full of horror and pain. In 1785, exactly 100 years after the Battle of Sedgemoor, Bridgwater was the first town in England to petition the British parliament for the abolition of slavery. Their pleas fell on death ears, as too much money was being made by important people, but they were in the vanguard of history. The anti-slavery movement, led by William Wilberforce, would end British involvement in the slave trade (but not slavery), in 1807.

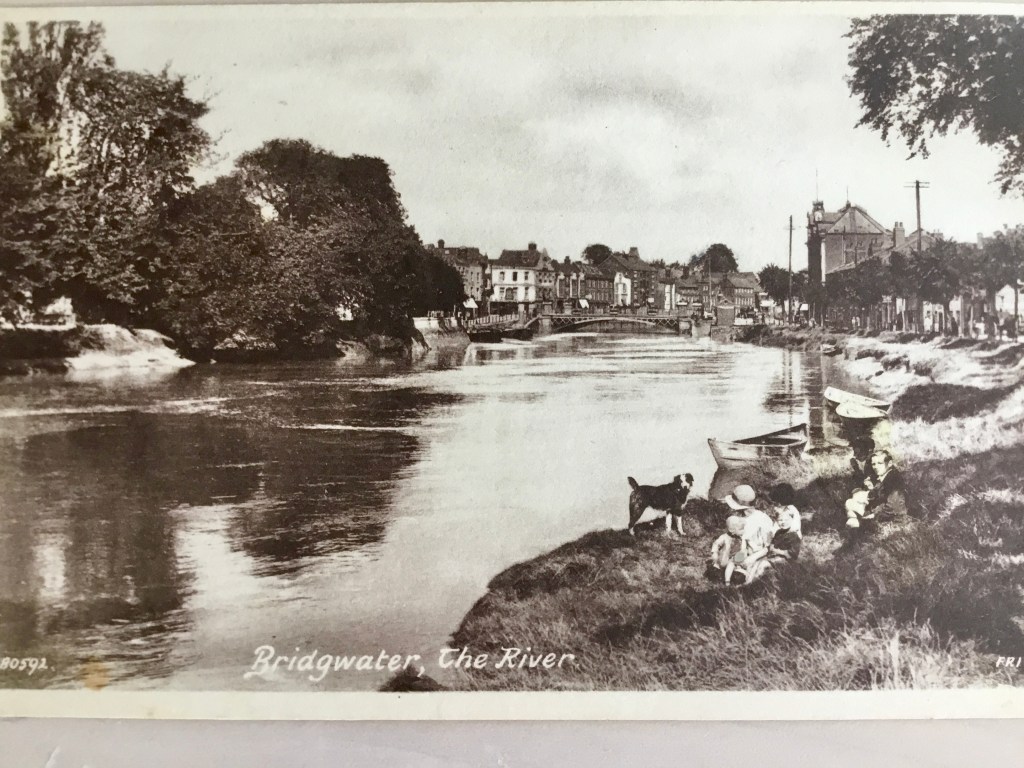

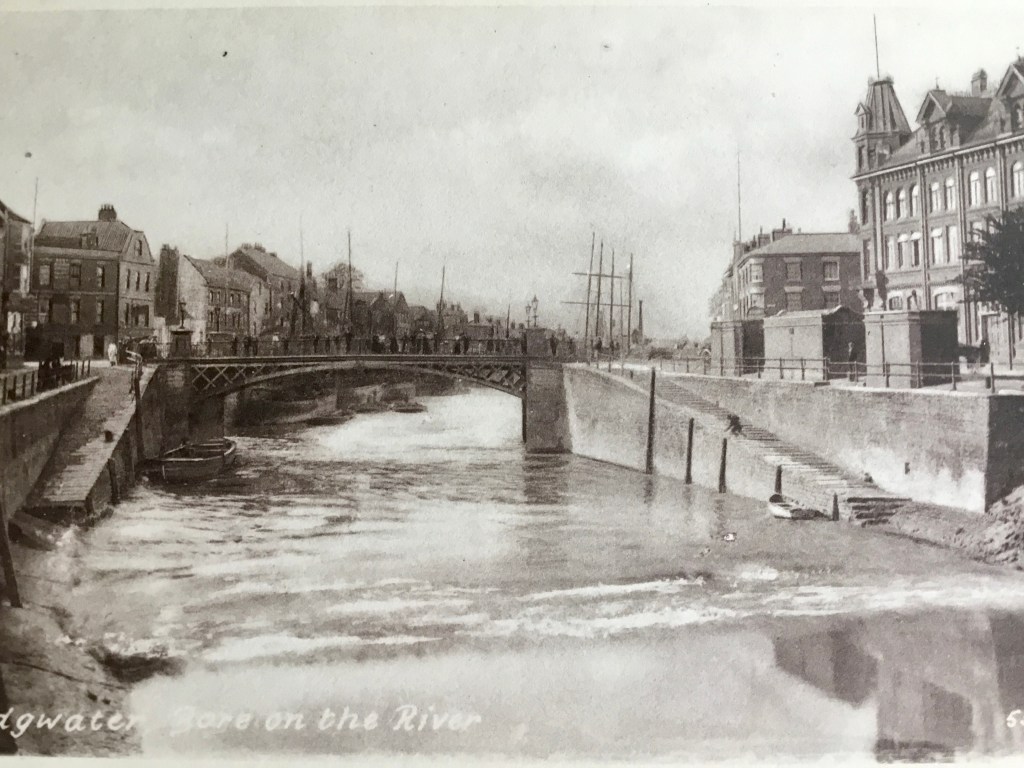

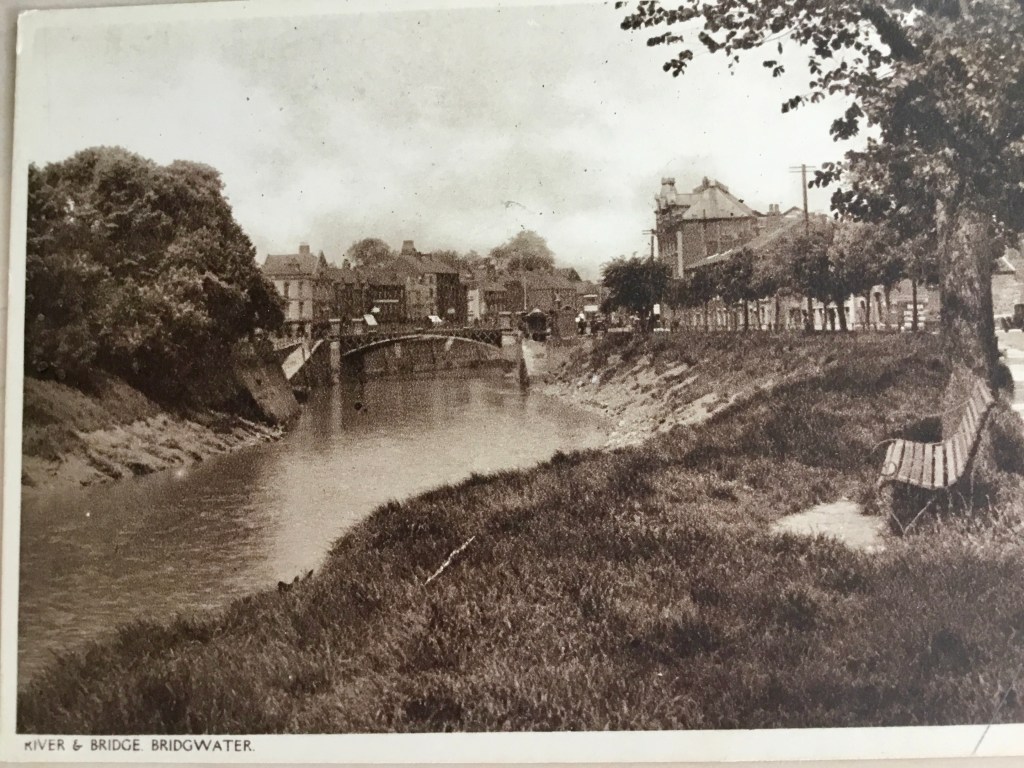

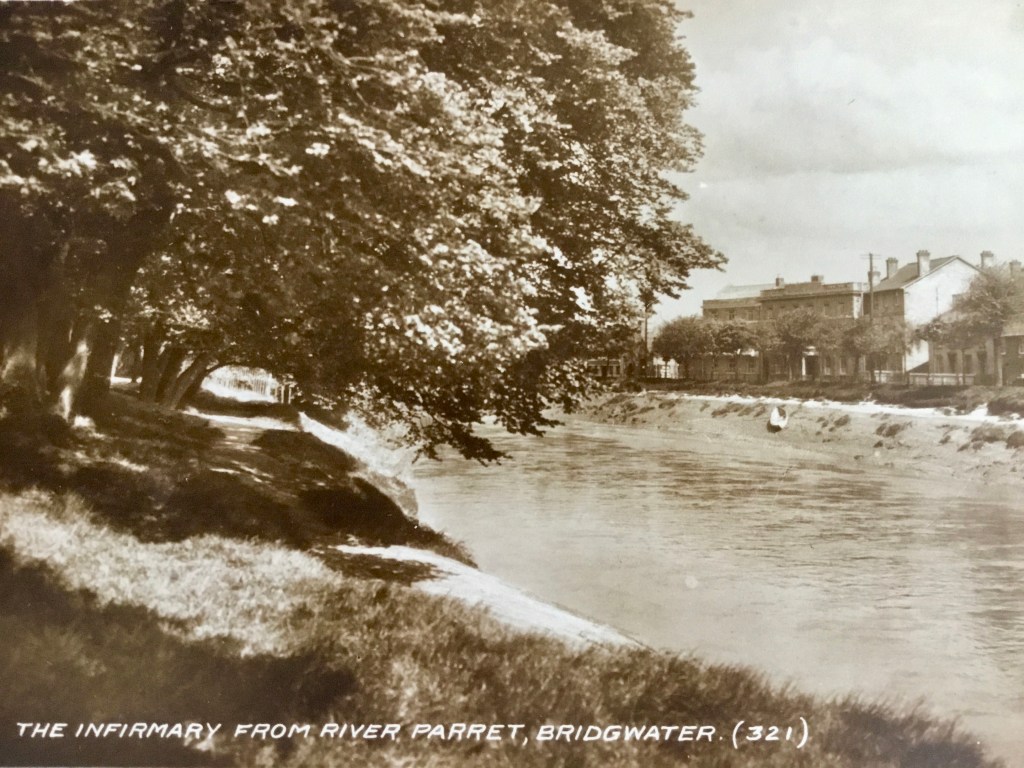

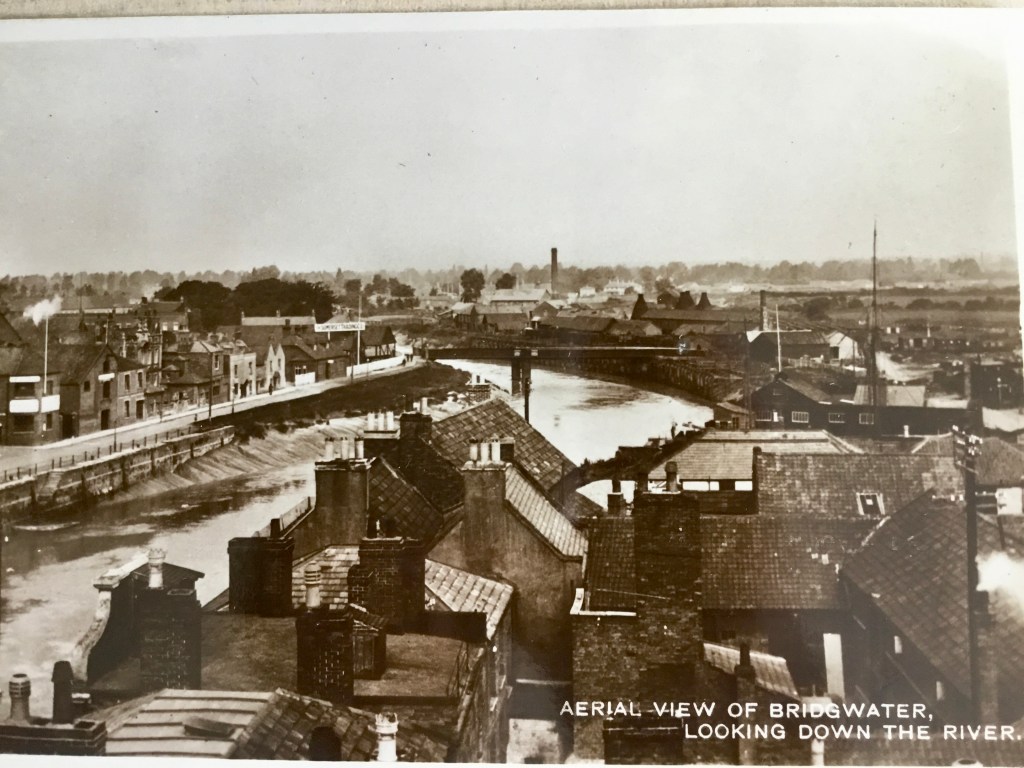

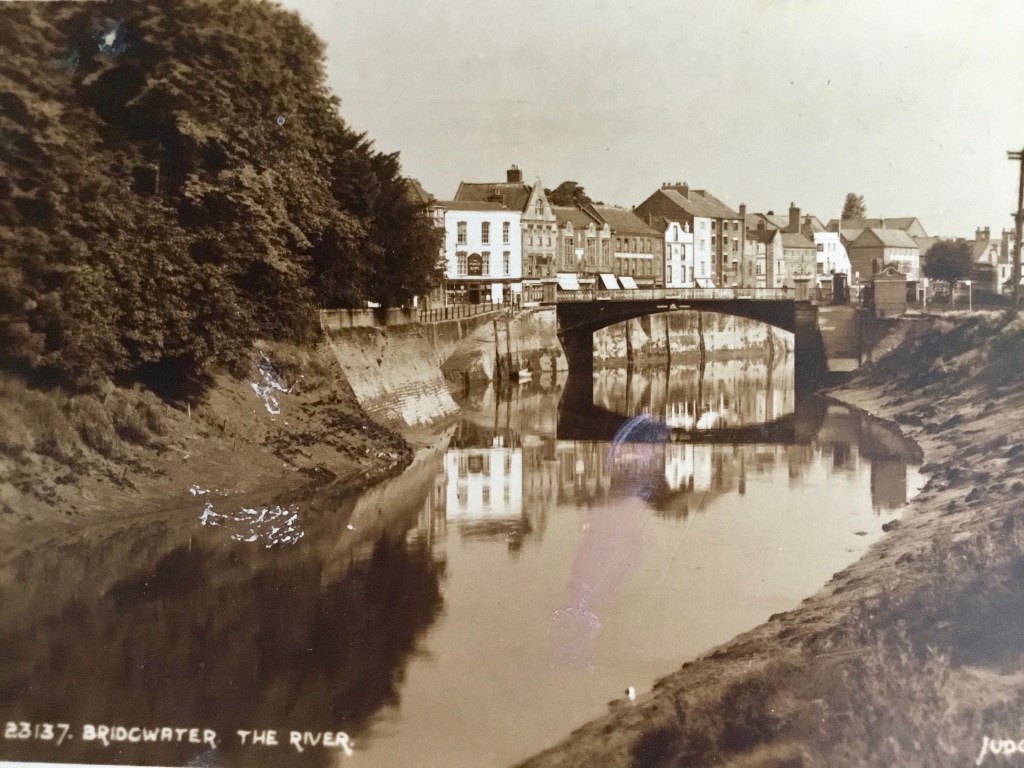

Bridgwater did decline as a port, in part due to the silting of the River Parrett, but it was a slow process. During my time living in Prince Edward Island, on the Canadian East Coast, I learned that it was Island timber, imported through the Port of Bridgwater, that was used for the railway ties on Brunel’s Great West Railway. There is another linkage with the Maritimes. The Bay of Fundy off the coast of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, and the Bristol Channel, feature vast shallow bays which give rise to a tidal bore. I have never seen the one in Bridgwater (just the postcard below), but have seen it in Moncton, New Brunswick.

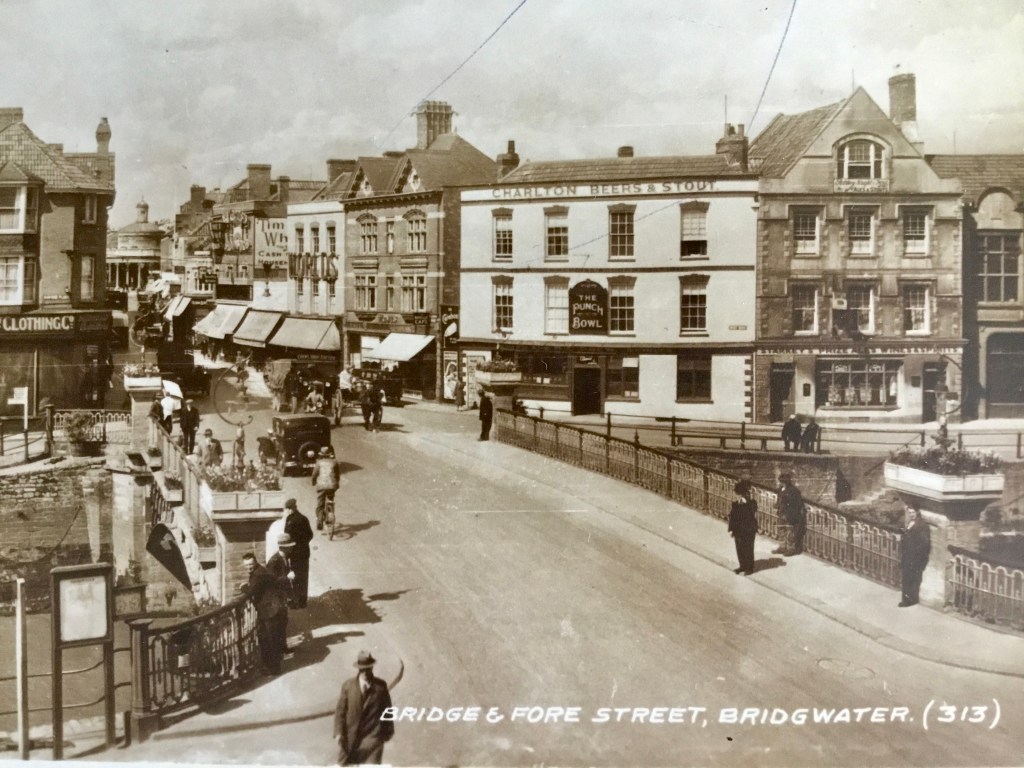

I am ending this post with my (late) Mother’s postcard collection which depict Bridgwater scenes (including the bore), taken mostly in the 1940s and 1950s. I would also like to give credit to the Bridgwater Past and Present Facebook page, and the Bridgwater civic website, for much of the historical information presented above.