Who can disbelieve in animism in Polynesia?

A short story written by Marjorie Frost. This was originally published in “The Bridgwater Irregular”, a journal produced by a writers workshop at Bridgwater College. It was inspired by her voyage from New Zealand to England in 1953 when the vessel stopped briefly at Pitcairn Island. Although a short story, it is quite lurid with several plot twists.

The cold sea mist made the rocks of the cave glisten with subdued colours. It haloed Maya’s straight, Polynesian hair with droplets of silver. She was thirty years old – her features already expressionless, blunted by an inner resignation and sadness.

Only her hands and eyes moved as she carefully built up a pyramid of palm fronds and bark with fragments of oily coconut shell, some with the white meat still adhering.

She had been on this nearly barren island, that rose like a whales back from the South Pacific , for fourteen years; ever since Fletcher Christian and his fellow mutineers had sought refuge here with a handful of native girls from Tahiti. At that time the barren inhospitable look of the Island, with its grey cliffs rising straight and formidable from the sea, assured their safety from British law. Since then it had become their prison – for Maya a prison with a harsh and brutal warder. It was Caleb who had abducted her from the sunlit beaches of Tahiti, who was avoided by the remainder of the crew for his sudden vicious temper, his ape-like features, and his strength.

All this Maya accepted, just as she accepted the vicissitudes of the weather and the uncertainty of their food supplies. Like her much loved Mother, honoured and consulted by their tribe, Maya had the power of withdrawing from her physical self and transcending to a distant and remote level of existence.

Now the hidden sea damp cave had become her refuge and the source of all her joy. Here she repeated the ritual of fire making and the dimly remembered chant – swaying to the rhythm, each hand lightly holding her Mother’s totem stick, so that it, with her arms and body, formed a complete circle.

It was all she owned from the old happy life. A stick of dark polished wood, shaped like a boomerang, one end carved in the head of a fish, and the other in the head of a seabird.

Just at this moment it was laid aside as she worked intently to produce the first glowing ember to ignite her little pyramid, and just at this moment Caleb discovered her sanctuary. Standing behind her he felt the full force of fear and hatred of the unknown. Fear and hatred twisted together like snakes in his brain. He picked up Maya’s stick and with full force smashed skull and brain with the beak of the carved bird and threw her body to the waves.

The stick lay by a small pyre of ashes for 200 years before it was found by an enterprising islander who thought it might make a few shillings when the next passenger liner from New Zealand anchored off Pitcairn.

This major event in the islanders year took place a few weeks later when the New Zealand Shipping Company’s liner “Rangitoto” approached Pitcairn. Leaning on the rail Carl Grafton felt a moments unease, a darkness in the mind akin to the dark mass of the island as it loomed larger and closer. He was in fact the only living descendent of Caleb who had made his escape from the island after Mayas death. The abnormal intensity of his mood changes switched to elation and excitement as he checked past preparations and imminent action.

Armed with a medical report on his ailing wife which stressed her bouts of depression and suicidal tendencies, he had consulted the ships medical officer, and they had both agreed that only one days sedatives should be available at a time. This medical report naturally enough did not include the information that Moira Grafton was immensely wealthy.

Tonight the long boats from Pitcairn would be rowed out and the Islanders would swarm up the rope ladders, their large prehensile toes grabbing the rungs, their arms hung with baskets of pineapples, coconuts, and wood carvings for sale to the passengers.

Dinner that night would be delayed for half an hour, by which time the swift tropical twilight would be over, the Islanders returned, and the decks deserted while passengers dressed for dinner. It was then he intended to take his wife to the dark stern of the liner where the propellor churned the sea to a white foam and there to tip her light body into the sea.

Fate seemed to be on his side; the ship rolled as he passed the ships pharmacy and the door flew open. The room was empty perhaps for only a minute, but it took far less time than that to grab a bottle of barbiturates in his handkerchief and to throw some of the tablets away in a convenient washroom.

He handed the bottle carefully but cheerfully to his wife. “Old Dodsons given us a decent supply this time”. And he watched approvingly as she grabbed the bottle firmly and put it away in her cabin drawer.

“I hardly use any now, anyway” she said, “the sea air is doing me so much good”.

Again his cue had come at the right moment, and she agreed to a turn on deck before dinner. As they leaned over the stern rail he grasped her round the waist, and to his astonishment found her much heavier than he had anticipated. “Whatever are you doing?” Her high penetrating voice cut through the noise of the propeller – devastatingly loud. In a second he realized his peril – her screams would be heard before she hit the water. Panicking, he grabbed a curved stick lying in the scuppers at his feet. It was Mayas stick, dropped by an overly convivial Islander as he climbed the ships rail for home. One sickening crunch silenced his wife for ever, and a moment later a lifeless bundle sank into the churning foam.

Immediately on cue the dinner bell rang out, and he hurried down to take his place at the Captains table.

A menu must have been proferred, and a choice made, but whatever he might have eaten went unnoticed – his brain seemed to be writhing in his skull. Suddenly things clicked into place. Distracted by the dinner bell he had forgotten to throw that curved stick after his wife’s body. He rose from the table, and the worry on his face was real enough. “My wife should have come down by now. Please excuse me while I fetch her”.

Once on deck he raced to the shadows in the stern of the ship, and relief flooded through him as he saw the stick lying there waiting for him. He climbed high on the rail and flung it with all his might in the direction of Pitcairn.

The stick seemed to possess an unearthly momentum of its own, and its velocity increased as it returned in a huge curve of retribution to bury its bird’s beak in the man’s skull. His body slowly toppled from the rail into the waves below.

Inevitably the topic most discussed during the remainder of the voyage was the great love of Carl for Moira. In subdued and reverent voices they agreed that he could not face life without her. And wasn’t it wonderful that all her money had been left to foster the Polynesian arts, including that of wood carving.

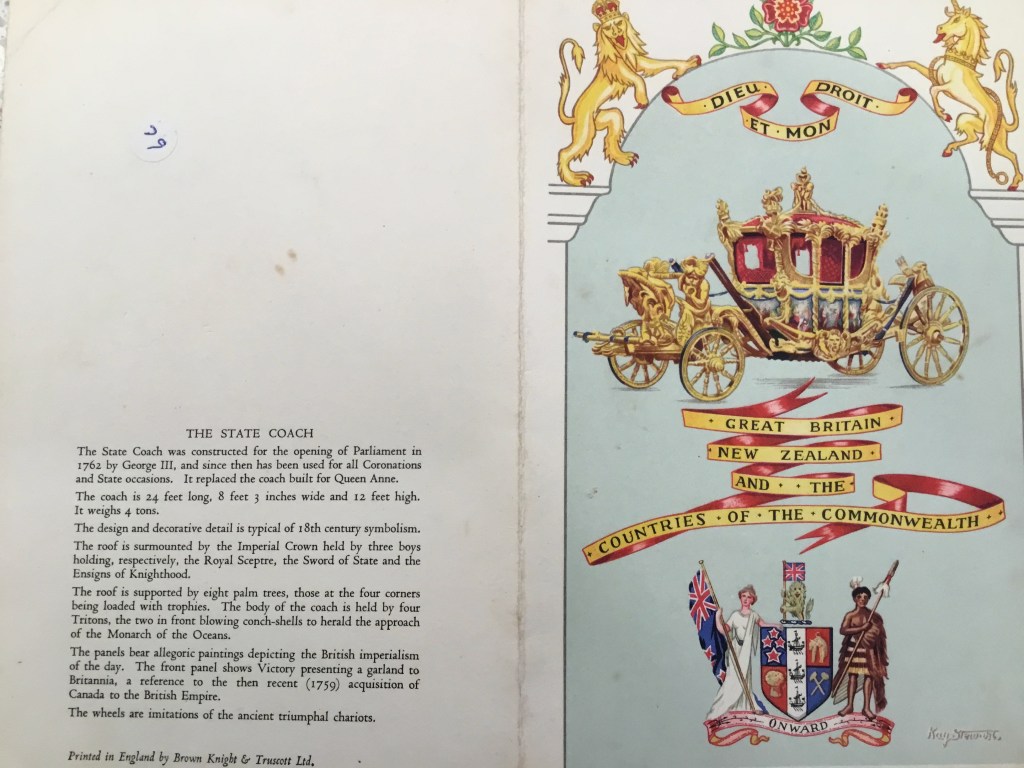

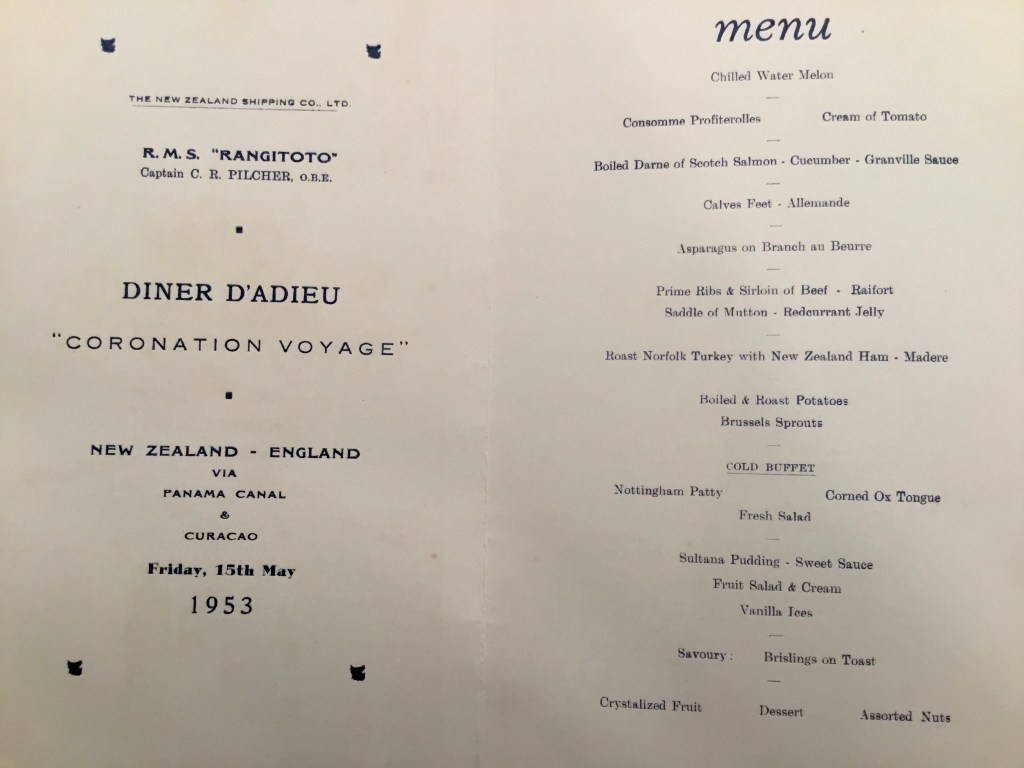

The dinner menu on the Rangitoto the night that Carl murdered his wife. The menu cover is displayed below.